Winter on Nantucket Island | Nantucket.net Blog

by Robert P. Barsanti

Winter comes to Nantucket with a gale from the north. The sky descends a few meters above our heads, the clouds tumble and the wind throws sand. If the wind is of a particular spirit, the temperature drops below freezing and the guys in shorts and “Let’s Go Brandon” sweatshirts begin to rethink their lifestyle choices. The air is about ten degrees cooler than in other places. In the mountains, a day in the 30s is crisp and clear, with just a hint of melting and bright sunshine glinting off the warm snow. Here, at the edge of the earth, it comes with darkness, wind and humidity. You can stand on the docks and watch the wind come to the top of the whitecaps and carry ocean effect snow. Then you dive inside.

The workers know it. They huddle in a line on the dock, dressed in layers of sweatshirts, carharts and beanies. They move foot to foot, look outside and wait to leave the ocean effect.

The boat brings the workers to Carharts and the sweatshirts and then sends them back at four o’clock with cigarettes and empty lunch boxes. When the yard closes, Nantucket has no more room for its workers. On a Saturday in January and February, a man will take care of the site. He’s finishing a window, nailing a few more shingles, or just cleaning up. But he will stay there, because the snow is blowing around him and the horizon is shrinking.

Winter lays bare the island; the ocean effect blows through our bones. We find ourselves with folded arms, naked with our skin tags, our scars and our cellulite open to the world. We have no excuses to the wind. The trash, left in a box in September, blew around the parking lot, caught in Rosa Rugosa’s bare arms and waving her corporate flag at the seagulls. The windows, carefully hidden by landscaping and foliage, shine on the street, if it is inhabited. Even dark houses cannot hide their interiors. We have no warm water embraces, no following winds, no light mists. In January, wind and water measure centuries, not you.

In the city center, Christmas is progressing painfully. Santa Claus and reindeer stroll through the windows, with chunky gold baubles and flowing red ribbons that wilt and fluff in the January breeze. Ralph Lauren celebrates Silver Christmas in the January snow. The “Seasons Greetings” remain after the season has died down and the lights have gone out. On the other hand, the fifty percent off sales pass, bringing something to do for the afternoon. Both sides of the street are lined with five- and ten-year-old pickup trucks and jeeps looking for a bargain on a shawl or a gift for the mother-in-law. The cobblestones will be empty at sunset.

We bounced down Main Street, lined with dark houses. The Christmas wreaths finally have their winter icing. At the earthly waves of the Quaker cemetery, the gust rose and swept the pious friends in whirlwinds and whirlwinds. On all other winter days, the field is Nantucket brown, edged in green, under a burst of blue (or gray). But in the wind it turned white.

The Madaket Road took us to a calm and cold past. No other cars came back to town, and none followed us. Instead, we rode under a board of starlings, clinging to the wire. After we passed the water tower, four deer popped out of the underbrush and ran down the middle of the street. We slowed down behind them, but like cyclists they pretended not to notice us. Fifty yards later, at a signal, they leaped over the fence and into the landscape.

We were socially alone at the dump. We parked where we wanted, nodded at other cars, and were able to drop plastic bottles and our pizza boxes into the correct chutes without incurring instructions. The “take it or leave it” was finally open. It has new shelves, lockers, a clean set of windows, and clothes spread across three different tables; one each for children, men and women. I rummaged through books while my son searched for DVDs and VCRs.

By the old shoes, two old acquaintances recognized each other. He leaned significantly on a cane, as she pulled her hat tighter, then tied her hood over it.

“It is cold.” She said. “You look well.”

“Yeah. Colder last week.

“Sure. It must be fine if we can remember worse.

They smiled and walked over to the books. I left them both at the slices, back covers, and sweatpants.

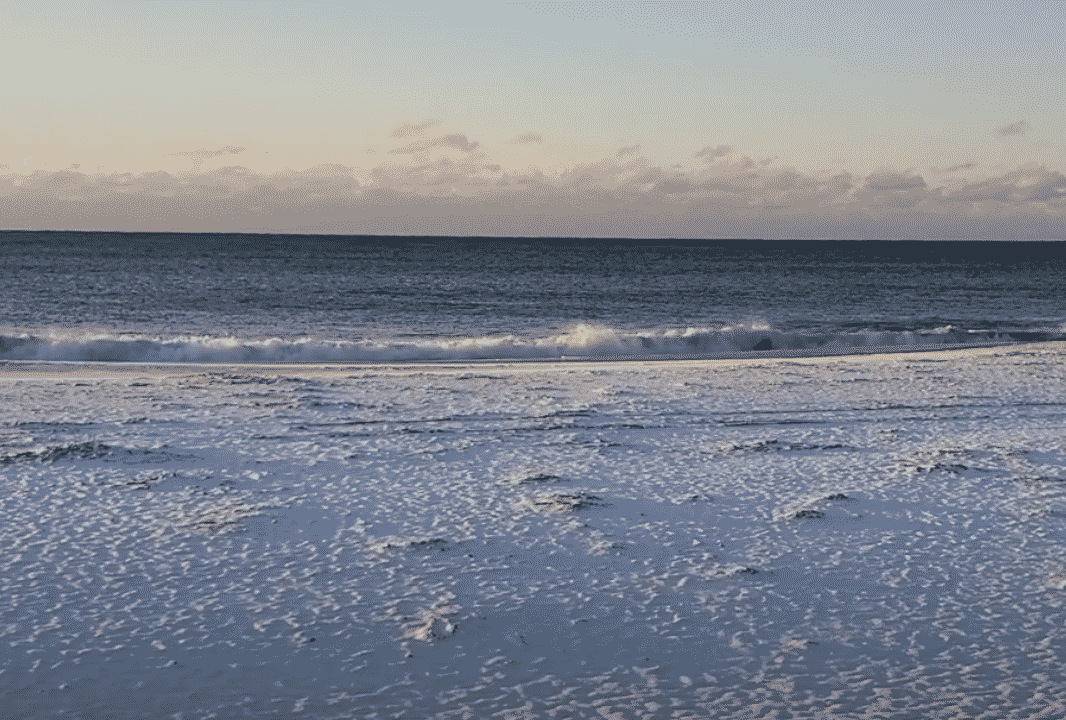

With a new DVD, shopping bag and Seamus Heaney’s translation of Beowulf, we continued to the end of the island. The ocean on the south shore pretended to be a lake. The snow continued its battery while half a mile offshore, the rays lit up the calm water. Naked and motionless, the ocean was waiting. Not for me, or anyone else with an expiration date, but maybe wind and tide. His whole life was hiding under the reflective gray sky. Granules of snow clung to seaweed and footsteps, shooting out of the imperfections in swirls and spirals.

Upon landing, the port and the cove remained as still and as silent. The mooring lines were empty, the water was calm, and a landless bird circled overhead.

We can have too much winter here. The naked truth of the island remains cold, wet and windy. All summer he dresses in flowers, work aprons and lilies. Time stands still in the Chicken Box line, and it will be 19 forever while winter measures time on a boat timetable, tide chart and barometer.

Human time is different. The boy and I entered the swimming competition. Our time arrives on the boat with all his swim team friends. This is measured in the afternoon, then in minutes, seconds and tenths of seconds of cheering and shouting at the pool. We were young, we were hot, we were sprinting down the lane without a breath in the summer bubble of a race. The ocean effect, in winter, brings us closer, whether at the swimming pool, at the store or at the Chicken Box. Winter can stay out and measure the slow ticking of the tide. Inside the bubble, we celebrate the vital tenths of a second of youth.